I have sorely neglected this blog over the past four or five months, and I apologize to my faithful follower! I could no longer stay away, however; I need to get some thoughts online. Besides, I love to hear myself type.

So I have been doing quite a bit of thinking over the past several weeks about the Occupy Wall Street (And Any Other Street That Takes Your Fancy) movement, and what it all means. I confess to an overarching mistrust of the "movement". While I think there are certain Occupiers that honestly hold a moral outrage against the turns the Western Capitalist system has taken, I believe that much of the movement is being instigated, supported and funded by people who have made their nut on the back of Capitalism and are now simply seeking to foment disorder, playing on the genuine angst of the 'rank-and-file' of the movement.

Setting this aside for the moment, I have been trying to assess the moral and spiritual underpinnings of the times and it comes down to a single word: anarchy, or to use the more theological word, antinomianism, i.e., lawlessness. The Occupiers are engaged in an act of lawlessness in response to a perceived—and in some fashion, at least, real—lawlessness in the financial/banking/investment capital industry. And I believe the cause is, at its core, a failure of the Church. Allow me to explain.

Capitalism has worked as a financial—not to say political—system for centuries because it is the only such system that takes into account the reality of human greed. The free market of Capitalism has historically allowed for the checks and balances necessary to contain the human sins of greed, avarice and gluttony.

Over the past 80 or so years we have watched the moral degradation of our culture, and it has pervaded every aspect thereof. There was a day when the every institution in the West was imbued, to say nothing of run on, Judeo-Christian moral law. Most of these institutions, but specifically the financial industry, began in the middle part of the last century to become amoral. This turned out to be a slippery slope down which we have slid over the past half-century; we now find ourselves in a land of our own making that is void of all morality. Some would see this as the liberation of our society, but it is quite the opposite; it is the enslavement thereof.

Anyone who has spent any time at all around children knows that one of the most fundamental things a parent or authority figure can give a child is a healthy sense of boundaries. A child without rules is terrified; that fear will often express itself as rage, and the child will act out in an effort to garner some response—any response—that will say, "This far you may go and no further".

Our culture (and here is where I fault the Church) has been allowed to systematically dismantle the moral code of society, the very things that hold us together and that keep us safe. The sanctity of marriage, the institution of the family, the "Golden Rule", the Ten Commandments—all have been marginalized, negated, ridiculed and removed until we are left with one law: the law of self-indulgence, i.e., if I want to do it, it is allowed. In the case of the financial industry, the caricature of Gordon Gekko, Michael Douglas' nefarious character in the iconic 1987 filmWall Street, has come to ascendancy; "Greed, for lack of a better word, is good!" And in our current culture, so is adultery, sex outside of marriage, gluttony, public nudity, trespassing, slander, usury and a nearly endless litany of what used to be called 'sins'. Sin is the occupational hazard of being a human. And it will have its way with us unless we bend the knee to a higher power.

And so we have thousands of people without boundaries, funded and supported by people without morals, crying out against an institution which is simply exhibiting the fruit of lawlessness. And I wonder how long it will take before this lawlessness, this anarchy, explodes into class warfare that will take out the final shaky underpinnings of the Republic in which we are blessed to live. And I wonder if we, the Church, have what it takes to wade into the anarchy with the Law of the One True King, and rescue this nation, perhaps even the world, from the dash to destruction. More on that in a coming post.

Friday, December 2, 2011

Monday, July 25, 2011

imagining god

In the past week I have had a couple of people flag an LA Times article at me that declares in no uncertain terms that science has now proven that God is a human invention. The empirical evidence is in; when we consider things of a religious nature, certain key areas of our brain light up. These areas turn out to be the same areas as light up when we process social interaction and relationships. This is proof that our need to engage in social activity and attachment is the same as our need to believe; we are as hard-wired for one as for the other. Faced with this revelation I find I have no choice but to abandon the ridiculous charade of being a purveyor of religion. I am turning in my shingle and looking for a job as a sanitation engineer. Or maybe a bartender. Or... perhaps not.

One of the most stunning statements from the article is this:

The notion that we are "born altruists who then have to learn strategic self-interest" could only have been proposed by someone who never had to get up for a 3 a.m. feeding. The altruistic infant would somehow understand, upon waking, that Mummy and Da need their sleep, that they will be certain, in the morning, to give the child as much food as he will need to survive, and that he should simply re-aquire his binky and return to blissful, altruistic slumber. Just where such an altruist would first learn "strategic self-interest" in the face of the doting nature of most new parents leaves me puzzled. The behavior of most parents, on the contrary, tends to reveal the better side of human nature—the denial of strategic self-interest. Of course, this evidence would not back up the 'non-God metanarrative', and so it must either be discounted or ignored.

After the page break the article makes the point that

What if science were to presuppose, rather than a [John] Lennonist notion of "no God, no religion", a God who, consistent with biblical evidence, created all things, declaring them "very good"(Genesis 1.31)? Might then one be able to see the sparking of the human brain under Persinger's "god helmet" as evidence that he was stimulating the very centers of the brain of the believer as are stimulated by the Holy Spirit? Could not the existence of these areas themselves be seen as evidence for God, rather than against Him? Rather than adaptive evolutionary triggers we have developed to insure that we all have a predisposition toward connectivity, may it not just possibly be, Drs. Persinger and Tomasello, that they are the product of "Intelligent Design"—that Whom we know as God, the Creator and Redeemer of the universe?

What if science were to presuppose, rather than a [John] Lennonist notion of "no God, no religion", a God who, consistent with biblical evidence, created all things, declaring them "very good"(Genesis 1.31)? Might then one be able to see the sparking of the human brain under Persinger's "god helmet" as evidence that he was stimulating the very centers of the brain of the believer as are stimulated by the Holy Spirit? Could not the existence of these areas themselves be seen as evidence for God, rather than against Him? Rather than adaptive evolutionary triggers we have developed to insure that we all have a predisposition toward connectivity, may it not just possibly be, Drs. Persinger and Tomasello, that they are the product of "Intelligent Design"—that Whom we know as God, the Creator and Redeemer of the universe?

What if St. Paul's dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus was, in reality, his temporal humanity being seized by the God who redeemed him?

What if St. Paul's dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus was, in reality, his temporal humanity being seized by the God who redeemed him?

Imagine that.

One of the most stunning statements from the article is this:

Michael Tomasello, a developmental psychologist who co-directs the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has also done work related to morality and very young children. He and his colleagues have produced a wealth of research that demonstrates children's capacities for altruism. He argues that we are born altruists who then have to learn strategic self-interest.This is profound evidence, once again, of the truism (attributed to Abraham Maslow) that when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Tomasello, and others of his ilk have begun their research with a premise. Their overarching metanarrative is that there is no God. Thus, every link in the chain of evidence reinforces that belief (or better, lack thereof), until at the end of the day their point of view is unassailable.

The notion that we are "born altruists who then have to learn strategic self-interest" could only have been proposed by someone who never had to get up for a 3 a.m. feeding. The altruistic infant would somehow understand, upon waking, that Mummy and Da need their sleep, that they will be certain, in the morning, to give the child as much food as he will need to survive, and that he should simply re-aquire his binky and return to blissful, altruistic slumber. Just where such an altruist would first learn "strategic self-interest" in the face of the doting nature of most new parents leaves me puzzled. The behavior of most parents, on the contrary, tends to reveal the better side of human nature—the denial of strategic self-interest. Of course, this evidence would not back up the 'non-God metanarrative', and so it must either be discounted or ignored.

After the page break the article makes the point that

[S]cientists have discovered neurological explanations for what many interpret as evidence of divine existence. Canadian psychologist Michael Persinger, who developed what he calls a "god helmet" that blocks sight and sound but stimulates the brain's temporal lobe, notes that many of his helmeted research subjects reported feeling the presence of "another." Depending on their personal and cultural history, they then interpreted the sensed presence as either a supernatural or religious figure. It is conceivable that St. Paul's dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus was, in reality, a seizure caused by temporal lobe epilepsy.

What if science were to presuppose, rather than a [John] Lennonist notion of "no God, no religion", a God who, consistent with biblical evidence, created all things, declaring them "very good"(Genesis 1.31)? Might then one be able to see the sparking of the human brain under Persinger's "god helmet" as evidence that he was stimulating the very centers of the brain of the believer as are stimulated by the Holy Spirit? Could not the existence of these areas themselves be seen as evidence for God, rather than against Him? Rather than adaptive evolutionary triggers we have developed to insure that we all have a predisposition toward connectivity, may it not just possibly be, Drs. Persinger and Tomasello, that they are the product of "Intelligent Design"—that Whom we know as God, the Creator and Redeemer of the universe?

What if science were to presuppose, rather than a [John] Lennonist notion of "no God, no religion", a God who, consistent with biblical evidence, created all things, declaring them "very good"(Genesis 1.31)? Might then one be able to see the sparking of the human brain under Persinger's "god helmet" as evidence that he was stimulating the very centers of the brain of the believer as are stimulated by the Holy Spirit? Could not the existence of these areas themselves be seen as evidence for God, rather than against Him? Rather than adaptive evolutionary triggers we have developed to insure that we all have a predisposition toward connectivity, may it not just possibly be, Drs. Persinger and Tomasello, that they are the product of "Intelligent Design"—that Whom we know as God, the Creator and Redeemer of the universe? What if St. Paul's dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus was, in reality, his temporal humanity being seized by the God who redeemed him?

What if St. Paul's dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus was, in reality, his temporal humanity being seized by the God who redeemed him?Imagine that.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

amusing ourselves

I happened to StumbleUpon some photos the other day of the Six Flags New Orleans amusement park. There was an eeriness to the pictures, not unlike what you might feel standing on the porch of an abandoned Victorian house—sort of "Addams Family-esque" feel.

I happened to StumbleUpon some photos the other day of the Six Flags New Orleans amusement park. There was an eeriness to the pictures, not unlike what you might feel standing on the porch of an abandoned Victorian house—sort of "Addams Family-esque" feel.But what struck me most was the irrelevance of it all. In my mind there was something of an "interesting, but so what?" feel to the whole thing—not at all the same feeling as I get when looking at the washed-out and abandoned homes left in the wake of Katrina. I was reminded of the story of a Ugandan bishop being taken on a tour of Disneyland. At the end of one particular ride (not to be named, but let us say that the main character in the story would be lost without his hat and whip), upon disembarking, the bishop turned to his host and asked, "And how, exactly, does this glorify Jesus?"

I love Disneyland, Six Flags and amusement parks in general. But looking at those photos of Six Flags NOLA brought a realization of the near-vacuity of a culture that is, as Neil Postman wrote in the mid-1980s, "amusing ourselves to death". I was struck particularly by the millions of dollars worth of equipment and structures simply lying around rusting into oblivion, and the incongruity of the graffiti sprayed in several places: "NOLA rising".

It is significant that there has been no effort at rehabilitation nor even clean-up since August 25, 2005. It is as if folks understand, almost unconsciously, the values-statement any such work would make. I assume that the Six Flags corporate office has realized that any attempt to rebuild while the real lives of thousands of residents and former residents of "NOLA" are still, six years after the fact, desperately impacted would be a profound act of hubris bordering on the inhuman. As it stands, it is a reminder of how much we expend on things that have no eternal value, and a statement of something that we really do not care to think about if we can at all avoid it: the notion that there is much we hold in high regard that, when the wheels come off, really do not amount to anything at all.

There is in me a certain gratification that Six Flags New Orleans lies abandoned and rusting away. I like the personal reminder that, when it all comes down to it, amusing myself for the sake of amusement not only doesn't add much to my life, but can in fact diminish it in some deep and profound ways. Paul said it this way:

Finally brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things [Philippians 4.8, ESV].

Sunday, June 12, 2011

anxiously acting out

There has been a tragic revelation lately in news stories of politicians behaving badly. The absence of sense and morality, the public indiscretions exposed in national leaders such as the former governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger and New York Representative Anthony Weiner are only the latest in a long series of such events that include Newt Gingrich, John Edwards and Bill Clinton; and we must not forget they also include folks like Ted Haggard and Jimmy Bakker.

What possesses men like these to undertake such tragic lapses of judgement? And even more tragic, what possesses us to accept such men as leaders? Is there no place for, much less expectancy of, morality and upright behavior any more? What could possibly entice us to elect and/or follow such people and invest them with so much power and authority?

I have been reading the blogs and online news sources, and I see a trend that I find profoundly disturbing. There seems to be a proliferation of opinions that run along the lines of: "Well, it was only pornography" and "We all do it!", so "What's the big deal? Why are we such prudes?" To say that Rep. Weiner's indiscretion was "only pornography" is like saying of the 400,000 + acre Wallow conflagration in eastern Arizona, "Well, it's only a wildfire!"

The truth is that we, as a culture, are on an ever-accelerating societal revolution to abandon all moral living as something which "cramps our style" to use the vernacular of my youth. And the curious—even tragic—thing about this collision course with anti-nomianism is that we are steadily laboring to abandon the very thing we are crying out for. Any culture needs laws, particularly moral laws, in order to survive. The current trend, however, is toward anarchy, and everyone a law unto himself.

Edwin Friedman writes that we are a culture in deep anxiety. This chronic anxiety has caused us to have ceased to promote and follow healthy, well differentiated leaders, and instead to organize ourselves around a basic immaturity, to the point of selecting those least mature to be our leaders. Instead of looking to great hearts and minds to lead us, we gravitate toward the slick and the self-aggrandizing egos of those who have no sense that they are not above the law, and no shame except the shame of being caught out in their indiscretions.

And, tragically, the anxious society perpetuates its own anxiety, potential leaders are prevented from rising to the top through the systematic cultural sabotage of their resolve and the tearing down of any initiative that might cause them to rise above the crowd. Curously, and almost counter-intuitively, one of the primary examples of a society in regression (to use Friedman's term) is an over-sensitivity to potential hurt. In A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, Friedman writes:

What possesses men like these to undertake such tragic lapses of judgement? And even more tragic, what possesses us to accept such men as leaders? Is there no place for, much less expectancy of, morality and upright behavior any more? What could possibly entice us to elect and/or follow such people and invest them with so much power and authority?

I have been reading the blogs and online news sources, and I see a trend that I find profoundly disturbing. There seems to be a proliferation of opinions that run along the lines of: "Well, it was only pornography" and "We all do it!", so "What's the big deal? Why are we such prudes?" To say that Rep. Weiner's indiscretion was "only pornography" is like saying of the 400,000 + acre Wallow conflagration in eastern Arizona, "Well, it's only a wildfire!"

The truth is that we, as a culture, are on an ever-accelerating societal revolution to abandon all moral living as something which "cramps our style" to use the vernacular of my youth. And the curious—even tragic—thing about this collision course with anti-nomianism is that we are steadily laboring to abandon the very thing we are crying out for. Any culture needs laws, particularly moral laws, in order to survive. The current trend, however, is toward anarchy, and everyone a law unto himself.

Edwin Friedman writes that we are a culture in deep anxiety. This chronic anxiety has caused us to have ceased to promote and follow healthy, well differentiated leaders, and instead to organize ourselves around a basic immaturity, to the point of selecting those least mature to be our leaders. Instead of looking to great hearts and minds to lead us, we gravitate toward the slick and the self-aggrandizing egos of those who have no sense that they are not above the law, and no shame except the shame of being caught out in their indiscretions.

And, tragically, the anxious society perpetuates its own anxiety, potential leaders are prevented from rising to the top through the systematic cultural sabotage of their resolve and the tearing down of any initiative that might cause them to rise above the crowd. Curously, and almost counter-intuitively, one of the primary examples of a society in regression (to use Friedman's term) is an over-sensitivity to potential hurt. In A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, Friedman writes:

As with any chronically anxious family, there is in American society today an intense quickness to interfere in another's self-expression, to overreact to any perceived hurt, to take all disagreement too seriously, and to brand the opposition with ad hominem personal epithets (chauvinist, ethnocentric, homophobic, and so on).

Until we begin to recognize that we are desperately in need of leaders who are unafraid to lead, and to undertake the hard solutions to a society in free-fall versus making their decisions based on the latest poll and looking for the "quick fix", we will continue to find ourselves "led" by the fearful immature, those completely incapable of doing the hard work of truly leading. And those "leaders", whose souls recognize their own poverty, will continue to act out of their immaturity in self-destructive fashion.

Monday, May 2, 2011

justice and sorrow

There is a great deal of talk surrounding last night's tracking down and killing of Osama bin Laden by a task force of US Special Operations warriors. As followers of Jesus, we have much to consider about this event. The more we consider, the more we must realize that there are no easy answers, no easy positions. While we may be tempted to delight glibly in seeing the arch-terrorist put to death, or conversely to decry his killing as murder, we disciples must, before everything, approach this with prayer and a godly attitude.

The first thing we must realize is this: we are made in the image of God. Because of this, we are imbued with a strong sense of justice, the desire to see things set right and to applaud when we see justice done. And because we are God's agents in the world, it is up to us to do all we can to see justice brought about, and injustice destroyed.

The difficulty for us lies in knowing exactly what justice entails in every situation. In some cases it is clear and obvious. In other cases it is muddied, uncertain. One of the great theological minds of the previous century, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a man thoroughly convinced of the truth of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, was executed for his part in a plot to assassinate Adolph Hitler. in 2009 Scott Roeder, conservative Christian pro-life advocate, slew late-term abortion provider George Tiller. Tiller, who during the week killed gestational infants in their third trimester of growth, on Sundays was himself an usher at his church, a ministry in which he was engaged when Roeder shot him. The same Jesus who told Peter to put away his sword had just that very evening told His disciples to arm themselves (John 18.10-11, Luke 22.36-38).

What is certain is that Jesus laid down His life for Osama bin Laden, as surely as He did for you and me. The fact that bin Laden never availed himself of that sacrificial death for his sins does not change the fact that God loved him. I imagine His sorrow over bin Laden is not unlike that He expressed over Jerusalem (Matthew 23.37, cf. Luke 13.34). This, then, should be our first reaction—godly sorrow for a lost soul—before we allow ourselves the satisfaction of justice meted out.

For surely the death of Osama bin Laden is an act of godly justice, even though it may be dispensed by a team of Navy SEALs, upon the command of President Obama at the behest of the government of the United States of America by the will of the people of this land. As Jesus told Pilate, no one has any power or authority unless it is given him by God (John 19.10-11). Bin Laden's death is simple and long-delayed retribution for the thousands upon thousands of lives his plotting and scheming and planning and training have violently ended over the course of his nefarious career.

On another level his death was, it would seem, the one he chose. For surely he would've been taken prisoner and brought to trial—or perhaps a military tribunal—in the US had he surrendered on May 1, 2011 when the SEALs stormed his compound. Rather than be taken, however, he took up arms as he had vowed, and purchased for himself the death he had sworn himself to.

Nevertheless, even though justice has been served, our response as followers of our Lord should not be jubilation, but sadness—and only then satisfaction. D. A. Carson, in his book Love in Hard Places (ISBN-13: 9781581344257) has this to say:

The first thing we must realize is this: we are made in the image of God. Because of this, we are imbued with a strong sense of justice, the desire to see things set right and to applaud when we see justice done. And because we are God's agents in the world, it is up to us to do all we can to see justice brought about, and injustice destroyed.

The difficulty for us lies in knowing exactly what justice entails in every situation. In some cases it is clear and obvious. In other cases it is muddied, uncertain. One of the great theological minds of the previous century, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a man thoroughly convinced of the truth of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, was executed for his part in a plot to assassinate Adolph Hitler. in 2009 Scott Roeder, conservative Christian pro-life advocate, slew late-term abortion provider George Tiller. Tiller, who during the week killed gestational infants in their third trimester of growth, on Sundays was himself an usher at his church, a ministry in which he was engaged when Roeder shot him. The same Jesus who told Peter to put away his sword had just that very evening told His disciples to arm themselves (John 18.10-11, Luke 22.36-38).

What is certain is that Jesus laid down His life for Osama bin Laden, as surely as He did for you and me. The fact that bin Laden never availed himself of that sacrificial death for his sins does not change the fact that God loved him. I imagine His sorrow over bin Laden is not unlike that He expressed over Jerusalem (Matthew 23.37, cf. Luke 13.34). This, then, should be our first reaction—godly sorrow for a lost soul—before we allow ourselves the satisfaction of justice meted out.

For surely the death of Osama bin Laden is an act of godly justice, even though it may be dispensed by a team of Navy SEALs, upon the command of President Obama at the behest of the government of the United States of America by the will of the people of this land. As Jesus told Pilate, no one has any power or authority unless it is given him by God (John 19.10-11). Bin Laden's death is simple and long-delayed retribution for the thousands upon thousands of lives his plotting and scheming and planning and training have violently ended over the course of his nefarious career.

On another level his death was, it would seem, the one he chose. For surely he would've been taken prisoner and brought to trial—or perhaps a military tribunal—in the US had he surrendered on May 1, 2011 when the SEALs stormed his compound. Rather than be taken, however, he took up arms as he had vowed, and purchased for himself the death he had sworn himself to.

Nevertheless, even though justice has been served, our response as followers of our Lord should not be jubilation, but sadness—and only then satisfaction. D. A. Carson, in his book Love in Hard Places (ISBN-13: 9781581344257) has this to say:

The only rejoicing being done over the death of Osama bin Laden ought to be the glee of the demonic forces of darkness, who this day claimed another soul for eternal torment. And that, indeed, is a tragedy worthy of godly lament.

He is an evil man, and he must be stopped, but he is a man, and we should take no pleasure in destroying him. Vengeance is the Lord’s alone.Do not offer the alternative, “Should we weep for Osama bin Laden or hold him to account for his genocide and prevent him from carrying out his violent intentions?”The right answer is yes.

Friday, April 29, 2011

royals? really?

I have been noting with something approaching bemusement the hoo-hah regarding the Royal Nuptials so recently concluded in the wee hours (PDT) of this morning, and trying to figure out what all the fuss is here in the US. Facebook is rife with commentary and comedy. I have seen several statuses asking the question, "What's your Royal Wedding name?", inviting friends to combine the names of dead relatives with dead pets and street names to come up with a high-falutin name worthy of, ahem... Will and Kate's guest-list. The wife of one of my friends hosted a party to which the guests wore their wedding gowns to watch the event together.

I have been noting with something approaching bemusement the hoo-hah regarding the Royal Nuptials so recently concluded in the wee hours (PDT) of this morning, and trying to figure out what all the fuss is here in the US. Facebook is rife with commentary and comedy. I have seen several statuses asking the question, "What's your Royal Wedding name?", inviting friends to combine the names of dead relatives with dead pets and street names to come up with a high-falutin name worthy of, ahem... Will and Kate's guest-list. The wife of one of my friends hosted a party to which the guests wore their wedding gowns to watch the event together.I have been pondering all of this and have concluded that the Royal Wedding is much like St. Patrick's Day, during which, of course, everyone is Irish. In the same way, for the Royal Wedding, we are all loyal subjects of the Crown of England, cheering on the new Prince and Princess William, Duke of Cambridge with all vigor and stiff upper lips and whatnot. Of course, we pay no attention to the conflict this must set up within us as good Irish (that was so last month)!

Now, don't get me wrong; they seem to be a sweet couple, and I pray them a long and loving marriage in defiance of the statistical odds, and the tragedies of less recent royal marriages. And we all love pageantry, don't we? I mean, look at how we dress up our children for preschool "graduations" these days? We seem starved for pomp and circumstance.

But the question arises for me, and I wonder that it doesn't for every American: Didn't we undertake a war 235 years ago in defiance of the notion of being subject to the Crown? I seem to recall that some very smart and sincere men penned a little document called the Declaration of Independence, wherein some words were written about being "Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown." I know this because I spent a great deal of time as a child memorizing the dialogue from Stan Freberg Presents The United States of America Part One: The Early Years, wherein Tom Jefferson attempts to get Ben Franklin to sign off on the document before the 4th of July holiday ("You're so skittish! Who possibly could care if you do?" "The Un-British Activities Committee, that's who!"). I mean, what else are you going to do when you're 15 and you are imprisoned in a one-room cabin for weeks on end when you hate fishing and the only other things you have to entertain you are a .22 rifle and the Big Stinky Fly Trap?

So I'm trying to figure out this fascination with the Royals when it occurs to me: we, even those of us steeped in Independent America, are longing for a King. We mostly don't even realize it, because we have so long drunk at the tap of Independence that we think we are quenching our thirst for fountains of Living Water, when all we are doing, really, is sipping from a muddy cup. I am proud to be an American. I believe America was formed from the embodiment of good and godly principles of Christian faith. I believe we have done some of the greatest good a nation can possibly do throughout our short history. But I believe there is Someone larger than the United States of America to Whom I owe my fullest allegiance, and even my very life.

We are in the midst of celebrating the Resurrection of this King, and our resurrection with Him, who follow Him. He is the true King of all kings, the Real Royal of which all earthly royals are but types and shadows. He is the King we long for, even though we may not know it, even though we deny it; somewhere within us we know we need Him, and we desire to be subjects of His Kingdom. This is what we are created for; this is our deepest and most magnificent Obsession. And under His reign, we ourselves, simple independent commoners, become royals. A blessed Eastertide to all.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

...or what's a heaven for?

There has been so much heat—and no small amount of light, as well—throughout the Interwebs surrounding Rob Bell's latest book, Love Wins, that I feel compelled to say something about the subject. Not about the book, mind you, nor even about Bell himself. I have not read Love Wins, and I honestly have no intention of so doing. There are some excellent reviews out there, if you are interested. I, though, find it difficult enough to keep up the good fight of reading things I believe will increase my knowledge and wisdom regarding the things of the Kingdom of God. To spend any great amount of time reading that with which I must necessarily do mental and theological battle is for me misuse my time, apologetics not being my prime calling.

There has been so much heat—and no small amount of light, as well—throughout the Interwebs surrounding Rob Bell's latest book, Love Wins, that I feel compelled to say something about the subject. Not about the book, mind you, nor even about Bell himself. I have not read Love Wins, and I honestly have no intention of so doing. There are some excellent reviews out there, if you are interested. I, though, find it difficult enough to keep up the good fight of reading things I believe will increase my knowledge and wisdom regarding the things of the Kingdom of God. To spend any great amount of time reading that with which I must necessarily do mental and theological battle is for me misuse my time, apologetics not being my prime calling.

While the idea of "know thine enemy" is a valid one, the depth of that knowing is something we must carefully judge. And while I am pretty certain I would not classify Bell as "enemy", he seems to ascribe to certain—well, "fuzzy" is not too unkind an adjective, I think—ways of thinking about God and the Gospel. So much of what passes as theology today is what H. Richard Niebuhr described as liberal thought: the idea that "A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross"—in other words, a theology without theology, or at least such as could be recognized by the Fathers of faith. Add to this my belief that the best way to spot the counterfeit is, as the Secret Service knows, to get intimately familiar with the real, and I feel the need to reflect.

So, it seemed fitting and proper to me, during this Holy Week, to spend a little time looking at the truth of the Gospel, and why it is important. In 900 words or less. Bold, you must admit, if somewhat audacious. Please keep your appendages within the vehicle, and remain seated at all times until the ride has come to a complete stop.

The first thing to remember about the Gospel is this: it is an offense to the thinking of the world (cf. 2 Peter 2.6-8, 1 Corinthians 1.18-31). Nothing about "dying in order to live" makes any sense to the world. The notion—in a culture where it is imperative that no one ever feel bad about himself—of being broken, or (God, or Whoever, forbid!) a sinner and in need of being fixed or "redeemed", is anathema.

The Gospel, however, is clear: every human being, save One, is a fractured image of humanity, of what we were intended to be—a clear reflection of God (cf. Genesis 1.26). Every one of us. Everyone. We have rebelled against God, and in the reality of creation, those who rebel against the Creator are doomed to die. That death, again according to Scripture, is eternal and tormenting. This is the bad news; and we have to deal with the bad news before we can approach the Good News. That bad news can be summed up thusly: Without direct intervention from a Source outside ourselves, we shall surely be lost, tormented in death forever unending. This thought does not make people happy. Nor is it intended to. It is, however, the truth; and it is offensive.

But it is not the end of the story. Once we acknowledge the bad news we can pass through it to the Good News. And the Good News is this:

For God so loved the world, that He gave His only Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through Him. Whoever believes in Him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God" (John 3.16-18 ESV).

The short version: God does not desire that we suffer the penalty we ourselves have incurred, but has indeed made a way that we should not have to suffer that penalty through the work of God the Son, Jesus Christ. Contrary to the false premise some theologians put forth, God does not condemn His creatures to Hell; He rather provides the means, through the shedding of His own blood and the giving up of His own life, for us not to have that horrific never-ending end.

God is holy, and His holiness cannot, by very nature, abide that which is unholy. Jesus is completely holy. He is also completely human. Because of that, humanity has access once again to the One True and Holy God. We are saved, not by our own doing, and not because God is too nice to let anyone spend the eternal life He gave him in the torture of unending death. No, we are saved through trusting in God's unending, unquenchable, unconditional, unfathomable love revealed through the death of God the Son by the horrific torture of the Cross. While our lot is death forever, in Jesus Christ we may have life forever. Which will we choose?

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

wisdom like lightning...

I ran across this quote from Benjamin Franklin today, and it struck me how often I violate these simple principles:

I have often considered the art of conversation, and sometimes felt as though I were a hacker at it. While I am seldom at a loss for words, it is often the art of soliloquy that I embody. I have on more than one occasion found myself apologizing and recommending those objects of my verbosity with the misfortune to be standing around me to that support group for loved ones of preachers: On-and-onAnon. I was, honestly, convicted in every turn by Ben. Allow me to take him point by point:

To admire little, to hear much—which is to say I must not be enamored of my own thoughts and words nor necessarily of those around me simply because I may admire or respect them. It is easy for me to fall in love with my own ideas; but it is also easy for me to make the mistake of not thinking critically about the ideas of others in whom I invest high praise. The best prevention, as Franklin notes, is to listen before assessing, to get all the information possible.

Always to distrust our own reason, and sometimes that of our friends—it is nearly impossible to see around our own paradigm, to escape our own worldview. And those with whom we share fellowship most readily are likely to be, at least in part, within that same paradigm. It is well that we let our friends speak into our lives, but we need to apply the same critical thinking to their ideas that we apply to strangers or mere acquaintances.

Never to pretend to wit, but to make that of others appear as much as possibly we can—one of my professors at seminary was an absolute master at this. I always walked away from a conversation with him feeling like he felt I was the smartest guy in the room. It was not that he was without wit; quite the contrary. But he was never concerned with making everybody else realize that he was brilliant and clever. He drew it out of everyone with whom he spoke. We were all giants with him. And in the process, he formed our minds and our theology. May I someday attain to such wit.

To harken to what is said and to answer to the purpose—how many times do I listen with half an ear while preparing in my mind what I am going to say next? More than I care to admit. Or, if I'm not thinking about what I will say, I'm thinking about how the other party could better have said what it was she is saying. Rude! I find that when I focus on the other person's words and do my best to understand the underlying thoughts of what he is saying, then give myself some space before responding, that conversations are much more meaningful and engaging.

For me, this boils down to St. Paul's letter to the Philippians: Do nothing from rivalry or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves [Philippians 2.3 ESV].

______________________

The great secret of succeeding in conversation is to admire little, to hear much; always to distrust our own reason, and sometimes that of our friends; never to pretend to wit, but to make that of others appear as much as possibly we can; to hearken to what is said and to answer to the purpose. (1.)

I have often considered the art of conversation, and sometimes felt as though I were a hacker at it. While I am seldom at a loss for words, it is often the art of soliloquy that I embody. I have on more than one occasion found myself apologizing and recommending those objects of my verbosity with the misfortune to be standing around me to that support group for loved ones of preachers: On-and-onAnon. I was, honestly, convicted in every turn by Ben. Allow me to take him point by point:

To admire little, to hear much—which is to say I must not be enamored of my own thoughts and words nor necessarily of those around me simply because I may admire or respect them. It is easy for me to fall in love with my own ideas; but it is also easy for me to make the mistake of not thinking critically about the ideas of others in whom I invest high praise. The best prevention, as Franklin notes, is to listen before assessing, to get all the information possible.

Always to distrust our own reason, and sometimes that of our friends—it is nearly impossible to see around our own paradigm, to escape our own worldview. And those with whom we share fellowship most readily are likely to be, at least in part, within that same paradigm. It is well that we let our friends speak into our lives, but we need to apply the same critical thinking to their ideas that we apply to strangers or mere acquaintances.

Never to pretend to wit, but to make that of others appear as much as possibly we can—one of my professors at seminary was an absolute master at this. I always walked away from a conversation with him feeling like he felt I was the smartest guy in the room. It was not that he was without wit; quite the contrary. But he was never concerned with making everybody else realize that he was brilliant and clever. He drew it out of everyone with whom he spoke. We were all giants with him. And in the process, he formed our minds and our theology. May I someday attain to such wit.

To harken to what is said and to answer to the purpose—how many times do I listen with half an ear while preparing in my mind what I am going to say next? More than I care to admit. Or, if I'm not thinking about what I will say, I'm thinking about how the other party could better have said what it was she is saying. Rude! I find that when I focus on the other person's words and do my best to understand the underlying thoughts of what he is saying, then give myself some space before responding, that conversations are much more meaningful and engaging.

For me, this boils down to St. Paul's letter to the Philippians: Do nothing from rivalry or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves [Philippians 2.3 ESV].

______________________

(1.) The_great_secret_of_succeeding_in_conversation_is. (n.d.). Columbia World of Quotations. Retrieved March 29, 2011, from Dictionary.com website:http://quotes.dictionary.com/The_great_secret_of_succeeding_in_conversation_is

Monday, March 7, 2011

why not?

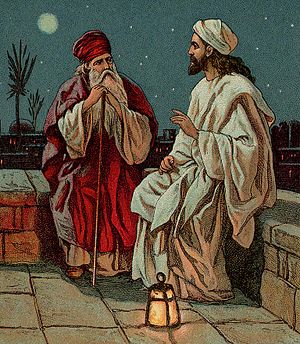

One of my readers... or perhaps I should better say "my one reader"... asked me to blog an answer to a posting at aish.com entitled Why Jews Don't Believe in Jesus. I don't really see myself as an apologist, except insofar as we each of us need always to be "prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you" (1 Peter 3.15). But as we interact with the culture around us, I think it is important that we understand the issues others might raise in contradiction to the truth of God. So, here is my thinking on the question.

First of all, the statement is a false generalization. While the argument could be made otherwise, a more honest name for the article might be: Why You Can't Believe in Jesus and Be a Jew. The subtle distinction here is one of dogmatic belief, to wit: "if you really were a Jew, or if you were a true Jew, you would not believe in such heresy." So, by argument, no true or real Jew believes Jesus is the Messiah. While this would be a more honest title, it still is false. We have historical evidence to the contrary.

First, in the Gospels, we have the stories of Nicodemus in the Gospel of John. And then we have the evidence of one of the great Pharisees of all time, Saul of Tarsus. Saul, by then known as Paul, gives his pedigree in Philippians 3, and also Acts 22. These two Pharisees, at minimum, prove that the generalization is false.

But there are also hundreds of thousands of Jews—one source says over a million—who have come to believe that Jesus, or Yeshua, to use the transliteration of His Hebrew name, is indeed the promised Messiah.

Even this, however, is not the linchpin of the argument against Jews believing in Jesus. The truth of the matter is that every one of Jesus' first disciples was a Jew. And this highlights a certain fact: there are very seldom any "pure" arguments for or against something. It is difficult to escape one's own paradigm and take a position based solely on dispassionate evidence. If I am setting out to prove that Jews don't believe in Jesus, I will likely fail to take into account evidence contradicting my premise. This is why it is vitally important that we listen to one another, and do not make our judgments in the vacuum of our own thoughts. And it is why Jesus told us, His disciples, not to meditate on what to say in defense of our position, but to trust the Holy Spirit to bring to mind what He would have us to say.

I expect that I will further fisk this article in future posts... stay tuned!

First of all, the statement is a false generalization. While the argument could be made otherwise, a more honest name for the article might be: Why You Can't Believe in Jesus and Be a Jew. The subtle distinction here is one of dogmatic belief, to wit: "if you really were a Jew, or if you were a true Jew, you would not believe in such heresy." So, by argument, no true or real Jew believes Jesus is the Messiah. While this would be a more honest title, it still is false. We have historical evidence to the contrary.

|

| Nick at Night... |

First, in the Gospels, we have the stories of Nicodemus in the Gospel of John. And then we have the evidence of one of the great Pharisees of all time, Saul of Tarsus. Saul, by then known as Paul, gives his pedigree in Philippians 3, and also Acts 22. These two Pharisees, at minimum, prove that the generalization is false.

But there are also hundreds of thousands of Jews—one source says over a million—who have come to believe that Jesus, or Yeshua, to use the transliteration of His Hebrew name, is indeed the promised Messiah.

Even this, however, is not the linchpin of the argument against Jews believing in Jesus. The truth of the matter is that every one of Jesus' first disciples was a Jew. And this highlights a certain fact: there are very seldom any "pure" arguments for or against something. It is difficult to escape one's own paradigm and take a position based solely on dispassionate evidence. If I am setting out to prove that Jews don't believe in Jesus, I will likely fail to take into account evidence contradicting my premise. This is why it is vitally important that we listen to one another, and do not make our judgments in the vacuum of our own thoughts. And it is why Jesus told us, His disciples, not to meditate on what to say in defense of our position, but to trust the Holy Spirit to bring to mind what He would have us to say.

I expect that I will further fisk this article in future posts... stay tuned!

Friday, February 25, 2011

more on being a chronically anxious society

I am continuing my reading in Edwin Friedman's book A Failure of Nerve, and am finding myself constantly nodding and wearing out my highlighter.

Friedman holds that the chronically anxious society will focus on the symptoms of its anxiety and mistake them for the causes of that anxiety—be they violence, crime, drugs, "red-vs.-blue", unemployment, etc.—rather than focusing on "the emotional processes that promote those symptoms and keep them chronic....

The only exit from chronic societal anxiety is through the path of acute and more painful examination of the causes of the anxiety. This requires a self-differentiated leader who has the vision to lead into and through the deep pain of systemic healing. Without this, the system will invariably choose the chronic but endurable pain of the symptomatic over the acute pain of healing—think "arthritis" vs. "hip replacement", or "toothache" vs. "root canal".

The church in the West is, I believe, undergoing this societal regression. We find ourselves reacting to the world around us, getting involved in battles with the culture, feeling the symptoms of being an organization that more and more is viewed as arcane, meaningless, pointless—even dangerous. Where Christianity was once the warp and weft of Western culture, we now find ourselves relegated to the rag-bin of society... at least in the culture as it is conveyed by the entertainment and news industries. As we feel our influence and even meaning slipping into the "laugh-track" category, we are more and more drawn to focus on the symptoms of our anxiety, ignoring the primary causes of the fear.

Many leaders are content to rail against the symptoms, be they abortion, divorce, pornography, the "big one" i.e., same-gendered sexuality, or any number of societal ills. But seldom do these leaders address the deeper cause: the Church's failure to engender discipleship in her members.

![]() H. Richard Niebuhr, in his seminal work Christ and Culture (1951), discussed five models of the influence of Jesus on culture. I believe the most accurate of those five models is that of Christ as Transformer of Culture. This model understands the role of Christians to be the conversion and redemption of culture so that all of society may be about the work of the Kingdom of God. It is only when Christians are faithfully following Jesus—acting as disciples, not just churchgoers—that this transformation is possible.

H. Richard Niebuhr, in his seminal work Christ and Culture (1951), discussed five models of the influence of Jesus on culture. I believe the most accurate of those five models is that of Christ as Transformer of Culture. This model understands the role of Christians to be the conversion and redemption of culture so that all of society may be about the work of the Kingdom of God. It is only when Christians are faithfully following Jesus—acting as disciples, not just churchgoers—that this transformation is possible.

Self-differentiated Church leaders must address this root cause of our chronic anxiety as the people of God in order to begin to relieve that anxiety so that the disciples of Jesus can fulfill their call to bring the transformative work of Jesus to the broken world around us.

Friedman holds that the chronically anxious society will focus on the symptoms of its anxiety and mistake them for the causes of that anxiety—be they violence, crime, drugs, "red-vs.-blue", unemployment, etc.—rather than focusing on "the emotional processes that promote those symptoms and keep them chronic....

[T]he more systemic chronic anxiety becomes in any [relationship system], the more likely that relationship system is to stay oriented toward its symptoms, or the more likely to engage in 'foreign entanglements'—wars and international crises for nations; intense struggles at neighborhood swimming pools, religious institutions or school boards for families—as a way to avoid facing the emotional processes that are driving that [relationship system] to become symptomatic" (Friedman, 60).

The only exit from chronic societal anxiety is through the path of acute and more painful examination of the causes of the anxiety. This requires a self-differentiated leader who has the vision to lead into and through the deep pain of systemic healing. Without this, the system will invariably choose the chronic but endurable pain of the symptomatic over the acute pain of healing—think "arthritis" vs. "hip replacement", or "toothache" vs. "root canal".

The church in the West is, I believe, undergoing this societal regression. We find ourselves reacting to the world around us, getting involved in battles with the culture, feeling the symptoms of being an organization that more and more is viewed as arcane, meaningless, pointless—even dangerous. Where Christianity was once the warp and weft of Western culture, we now find ourselves relegated to the rag-bin of society... at least in the culture as it is conveyed by the entertainment and news industries. As we feel our influence and even meaning slipping into the "laugh-track" category, we are more and more drawn to focus on the symptoms of our anxiety, ignoring the primary causes of the fear.

Many leaders are content to rail against the symptoms, be they abortion, divorce, pornography, the "big one" i.e., same-gendered sexuality, or any number of societal ills. But seldom do these leaders address the deeper cause: the Church's failure to engender discipleship in her members.

Self-differentiated Church leaders must address this root cause of our chronic anxiety as the people of God in order to begin to relieve that anxiety so that the disciples of Jesus can fulfill their call to bring the transformative work of Jesus to the broken world around us.

Monday, February 14, 2011

leadership in an age of anxiety

It is becoming clearer and clearer to me that the world is, as my coach Kirk Kirlin says it, accelerating toward the abyss—aboard a bullet-train to Hell, if you will. We who follow Jesus know that only in the radical transformation of society by the Truth of Jesus Christ can we hope to see the brakes applied to that train.

And yet most of us simply sit back and shake our heads, and wait for someone to take up the crusade.

I am forced to ask myself this question: Who will exhibit this leadership if not you? What, Don, are you waiting for—someone else to lead? (Well, yeah, frankly...)

In his book A Failure of Nerve, Edwin Friedman posits that we are living in what he terms "a society in regression"; that is, a society where the breakdown in relationships engenders chronic anxiety. Such a society is earmarked, Friedman says, "by increasing polarization, rigidity of belief, clouded vision, and an inability to change direction." He compares the scourge of political correctness to the Inquisition of medieval Europe, declaring both to be the result of a culture-wide regressive emotional state [p. 52]. This anxiety is characterized by five characteristics of chronically anxious families: intense reactivity of members to events and each other; herding, i.e., placing emphasis on togetherness above individuation and causing everyone to adapt to the least mature members; blame displacement, focusing on being a victim rather than taking personal responsibility for their own destiny and being; a low threshold for pain that breeds a quick fix mentality; and the lack of well-differentiated leadership, "which both stems from and contributes to the first four" [pp. 53-54].

In his book A Failure of Nerve, Edwin Friedman posits that we are living in what he terms "a society in regression"; that is, a society where the breakdown in relationships engenders chronic anxiety. Such a society is earmarked, Friedman says, "by increasing polarization, rigidity of belief, clouded vision, and an inability to change direction." He compares the scourge of political correctness to the Inquisition of medieval Europe, declaring both to be the result of a culture-wide regressive emotional state [p. 52]. This anxiety is characterized by five characteristics of chronically anxious families: intense reactivity of members to events and each other; herding, i.e., placing emphasis on togetherness above individuation and causing everyone to adapt to the least mature members; blame displacement, focusing on being a victim rather than taking personal responsibility for their own destiny and being; a low threshold for pain that breeds a quick fix mentality; and the lack of well-differentiated leadership, "which both stems from and contributes to the first four" [pp. 53-54].

The solution to the anxiety, Friedman declares, is real leadership. In order to break through the regression, real leaders must lead. This means that they must self-differentiate, that is, be sufficiently aware of and in touch with their own personhood that they are not drawn into the anxiety of those around them, and be willing to allow others the consequences of their own actions. When a self-differentiated leader comes to the fore, says Friedman, the anxiety of the system around him begins to lessen.

If we hope to see society transformed by the Gospel, we must see ourselves transformed by the Gospel. If we long to stop the train speeding toward Gehenna, then we must stand firm in our faith and

lead. We must not allow ourselves to be herded into a 'lowest common denominator" society, but rather accept responsibility for our own choices and recognize that we are called to be a non-anxious presence in the world around us.

And yet most of us simply sit back and shake our heads, and wait for someone to take up the crusade.

I am forced to ask myself this question: Who will exhibit this leadership if not you? What, Don, are you waiting for—someone else to lead? (Well, yeah, frankly...)

In his book A Failure of Nerve, Edwin Friedman posits that we are living in what he terms "a society in regression"; that is, a society where the breakdown in relationships engenders chronic anxiety. Such a society is earmarked, Friedman says, "by increasing polarization, rigidity of belief, clouded vision, and an inability to change direction." He compares the scourge of political correctness to the Inquisition of medieval Europe, declaring both to be the result of a culture-wide regressive emotional state [p. 52]. This anxiety is characterized by five characteristics of chronically anxious families: intense reactivity of members to events and each other; herding, i.e., placing emphasis on togetherness above individuation and causing everyone to adapt to the least mature members; blame displacement, focusing on being a victim rather than taking personal responsibility for their own destiny and being; a low threshold for pain that breeds a quick fix mentality; and the lack of well-differentiated leadership, "which both stems from and contributes to the first four" [pp. 53-54].

In his book A Failure of Nerve, Edwin Friedman posits that we are living in what he terms "a society in regression"; that is, a society where the breakdown in relationships engenders chronic anxiety. Such a society is earmarked, Friedman says, "by increasing polarization, rigidity of belief, clouded vision, and an inability to change direction." He compares the scourge of political correctness to the Inquisition of medieval Europe, declaring both to be the result of a culture-wide regressive emotional state [p. 52]. This anxiety is characterized by five characteristics of chronically anxious families: intense reactivity of members to events and each other; herding, i.e., placing emphasis on togetherness above individuation and causing everyone to adapt to the least mature members; blame displacement, focusing on being a victim rather than taking personal responsibility for their own destiny and being; a low threshold for pain that breeds a quick fix mentality; and the lack of well-differentiated leadership, "which both stems from and contributes to the first four" [pp. 53-54].The solution to the anxiety, Friedman declares, is real leadership. In order to break through the regression, real leaders must lead. This means that they must self-differentiate, that is, be sufficiently aware of and in touch with their own personhood that they are not drawn into the anxiety of those around them, and be willing to allow others the consequences of their own actions. When a self-differentiated leader comes to the fore, says Friedman, the anxiety of the system around him begins to lessen.

If we hope to see society transformed by the Gospel, we must see ourselves transformed by the Gospel. If we long to stop the train speeding toward Gehenna, then we must stand firm in our faith and

lead. We must not allow ourselves to be herded into a 'lowest common denominator" society, but rather accept responsibility for our own choices and recognize that we are called to be a non-anxious presence in the world around us.

Monday, January 31, 2011

the cost of discipleship

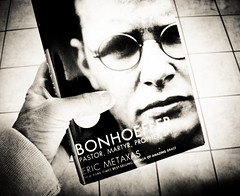

A dear friend of mine caused me to return to a book I had begun but had let languish, overcome by events and general busyness, since our vacation in late September: Eric Metaxas' Bonhoeffer—Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy. As soon as I picked it back up I was hooked all over again. Metaxas' writing is like butter on warm cornbread, and Bonhoeffer's life is absolutely fascinating.

The tome is daunting, 542 pages exclusive of photos, endnotes, bibliography and author's bio. Yet every time I pick it up I am hard-pressed to put it down. I confess that I have never been much of a biography reader; still, I find that I am blessed I know not how on my journey by studying the lives of others. And Bonhoeffer is strong medicine, indeed.

I bring Metaxas' book up because I have been thinking a lot about truth over the past several weeks, and wondering how we got to such a state as we find ourselves today. As I was reading on the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer I was struck by his assessment of the students at Union Theological Seminary,

and of the mainline Protestant churches in and around New York City when he studied in America in 1930-31. I was astonished to see evidence of the war against truth in his words:

There is no theology here... They talk a blue steak without the slightest substantive foundation and with no evidence of any criteria. The students... are completely clueless with respect to what dogmatics is really about. They are unfamiliar with even the most basic questions. They become intoxicated with liberal and humanistic phrases, laugh at the fundamentalists, and yet basically are not even up to their level (Metaxas, 101).

The theological atmosphere of the Union Theological Seminary is accelerating the process of the secularization of Christianity in America... [and] there is no sound basis on which one can rebuild after demolition. It is carried away with the general collapse (105).Metaxas writes of Bonhoeffer's observations:

In an attempt to be more sophisticated than the fundamentalists, whom they hated, [professors and students at Union] had jettisoned serious scholarship altogether. They seemed to know what the answer was supposed to be and weren't much concerned with how to get there. They knew only that whatever answer the fundamentalists came up with must be wrong. For Bonhoeffer, this was scandalous (103).Bonhoeffer found tepid faith in the churches he visited, with one exception:

Things are not much different in the church. The sermon has been reduced to parenthetical church remarks about newspaper events. As long as I've been here, I have heard only one sermon in which you could hear something like a genuine proclamation [of Christ and His atoning work for sin], and that was delivered by a negro (indeed, in general I'm increasingly discovering greater religious power and originality in Negroes). One big question continually attracting my attention in view of these facts is whether one here really can still speak about Christianity... There's no sense to expect the fruits where the Word really is no longer being preached (106).All this in 1931. This has been going on much longer than I think we imagined. And perhaps it was not new even then, considering the work that needed to be undertaken in the great councils of the early church. The real truth is that the Enemy can't come up with any new lies. Same girl, different red dress.

Let me encourage you to check out Metaxas' Bonhoeffer from your local library, or even purchase it for yours. You will find a great story of a great theologian, as told by a great writer. And you'll love to compare the cover picture with the author's photo on the flyleaf!

Monday, January 24, 2011

more of the truth

I mentioned in my last blog that I was reading A Place For Truth edited by Dallas Willard. This morning I read an essay by Os Guinness entitled Time for Truth. Guinness quotes Solzhenitsyn: "One word of truth outweighs the entire world," and the Charter '77 slogan, "Truth prevails for those who live in truth." Charter '77 was the work of the engineers of the Velvet Revolution (including Vaclav Havel) that overthrew the Communist government of Czechoslovakia in November of 1989.

Guinness contrasts the "impossible" revolution of truth over power with the present "crisis of truth" in Western culture, most particularly in its universities. The kind of truth that overthrew Communism is now considered dead. "At worst, it's socially constructed," says Guinness; "it's a testament to the community that said it and made it stick, and the power they had in expressing it."

Or, to oversimplify perhaps a bit: Truth is relative.

At the risk of letting Os Guinness write my blog, I want to share a fairly good chunk of his essay with you here, because I think it makes for excellent fodder for discussion. Beginning on page 40, he writes:

Likewise related is a crisis of ethics. Without truth as an objective reality, evil becomes relative. Guinness bemoans, "I've been on campuses where, to put it simply, today it is worse to judge evil than it is actually to do evil." The moral compass, bereft of truth, simply spins, the needle sweeping across a face with no markings.

These are frightening times; but we are not without recourse, we who believe in a core, central Truth, and the God Who is True. And Guinness encourages followers of Jesus to hang onto that very key idea: we follow God Who is True. When we place faith in this God, we wake up and shake off the nightmare of relativism ("I believe because it is true for me."), subjectivism ("I believe because I feel it deeply.") and pragmatism ("I believe it because it works for me."), and in the light of day believe simply because it is the truth. "The Christian faith is not true because it works; it works because it's true," says Guinness. "Ultimately truth, for both Jews and followers of Jesus, is finally a matter of who God is" [emphasis mine].

When we understand this, we can resist being manipulated by image and power. We can speak truth into relativism without fear of rejection. We can take the risk to ask the relativist to apply his principles universally, including to his own pet theory of the relativity of truth. We can point out the end result of relativistic truth: "If there's no truth and truth is dead, and knowledge is only power, then might makes right. The victory goes to the strong, and the weak go to the wall." But if there is indeed truth, then "truth prevails for those who live in truth."

...and that's a good thing.

Guinness contrasts the "impossible" revolution of truth over power with the present "crisis of truth" in Western culture, most particularly in its universities. The kind of truth that overthrew Communism is now considered dead. "At worst, it's socially constructed," says Guinness; "it's a testament to the community that said it and made it stick, and the power they had in expressing it."

Or, to oversimplify perhaps a bit: Truth is relative.

At the risk of letting Os Guinness write my blog, I want to share a fairly good chunk of his essay with you here, because I think it makes for excellent fodder for discussion. Beginning on page 40, he writes:

I want to argue that this crisis of truth is enormously important for both individuals and for the American Republic. Far from being Neanderthal and reactionary, truth is a very precious, simple, fundamental, human gift, without which we cannot negotiate reality and handle life. The truth is absolutely essential for a good human life. Equally important, truth is absolutely essential for freedom. And in the American Republic, where the challenge is not just becoming free but sustaining freedom, any people who would be free and remain free have to grapple seriously with the real challenge of truth.Concomitant with the crisis of truth is a crisis of character. Integrity is no longer in vogue; the only ideals are appearance, placement, "product identification." Guinness quotes Mark Twain: "In America, the secret of success is sincerity. If you can fake that, you've got it made," and Groucho Marx: "Hey, these are my principles, my moral principles. And if you don't like them, I've got others." If there is no objective truth, then there is no standard on which to build character.

Likewise related is a crisis of ethics. Without truth as an objective reality, evil becomes relative. Guinness bemoans, "I've been on campuses where, to put it simply, today it is worse to judge evil than it is actually to do evil." The moral compass, bereft of truth, simply spins, the needle sweeping across a face with no markings.

These are frightening times; but we are not without recourse, we who believe in a core, central Truth, and the God Who is True. And Guinness encourages followers of Jesus to hang onto that very key idea: we follow God Who is True. When we place faith in this God, we wake up and shake off the nightmare of relativism ("I believe because it is true for me."), subjectivism ("I believe because I feel it deeply.") and pragmatism ("I believe it because it works for me."), and in the light of day believe simply because it is the truth. "The Christian faith is not true because it works; it works because it's true," says Guinness. "Ultimately truth, for both Jews and followers of Jesus, is finally a matter of who God is" [emphasis mine].

When we understand this, we can resist being manipulated by image and power. We can speak truth into relativism without fear of rejection. We can take the risk to ask the relativist to apply his principles universally, including to his own pet theory of the relativity of truth. We can point out the end result of relativistic truth: "If there's no truth and truth is dead, and knowledge is only power, then might makes right. The victory goes to the strong, and the weak go to the wall." But if there is indeed truth, then "truth prevails for those who live in truth."

...and that's a good thing.

Monday, January 17, 2011

what is truth?

I was reading in Acts chapter 17 today about Paul's visit to Athens, and his apologetic for "the unknown god". As I read I wondered if such an approach would work in today's world here in the West. Paul was meeting a culture that, while spiritual, had never encountered Jesus. We, on the other hand, are dealing with a culture that has been pretty well inoculated against Jesus, in no small part due to the efforts of the erstwhile Christian Church to preach a watered-down gospel, lacking in power because it is lacking in discipleship. That, though, is a conversation best left for another post.

In the meantime, as I was trying to imagine a true Mars Hill experience in our present culture, I glanced over at my bookshelf and there saw a book which my bride had bought me entitled A Place for Truth: Leading Thinkers Explore Life's Hardest Questions,* a compilation of essays from the Veritas Forum, edited by Dallas Willard. I took it as a theophany, and opened it.

I love the way a new book feels, before the cover gets all curled and the pages all fanned out. I opened the book for the first time and began to read. The Veritas Forum began in 1992 when "a small group of Christians at Harvard hosted the university for a weekend of lectures and discussions exploring some of life's most important questions. Their hope was to restore within the university a space for asking deep questions, seeking real answers and building community around the search for truth" (p. 11). In the intervening years Veritas Forums have taken place at campuses throughout the US and Canada. Willard has compiled some of the best presentations therefrom.

In the opening essay of the book, Richard John Neuhaus declares:

I agree with Neuhaus that we who follow Jesus have an obligation and responsibility to declare that there is such a thing as truth. And the only way I see to avoid the pitfall becoming the enemies of civil discourse is to carry on those conversations in the context of relationships forged in our community.

I look forward to reading more of this book. I anticipate it will provide more fodder for this blog!

*InterVarsity Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8308-3845-5

In the meantime, as I was trying to imagine a true Mars Hill experience in our present culture, I glanced over at my bookshelf and there saw a book which my bride had bought me entitled A Place for Truth: Leading Thinkers Explore Life's Hardest Questions,* a compilation of essays from the Veritas Forum, edited by Dallas Willard. I took it as a theophany, and opened it.

I love the way a new book feels, before the cover gets all curled and the pages all fanned out. I opened the book for the first time and began to read. The Veritas Forum began in 1992 when "a small group of Christians at Harvard hosted the university for a weekend of lectures and discussions exploring some of life's most important questions. Their hope was to restore within the university a space for asking deep questions, seeking real answers and building community around the search for truth" (p. 11). In the intervening years Veritas Forums have taken place at campuses throughout the US and Canada. Willard has compiled some of the best presentations therefrom.

In the opening essay of the book, Richard John Neuhaus declares:

We Christians have an inescapable obligation to contend that there is truth, and that all truths finally serve the one truth. There is one truth because there is one God and one revelation of God in Jesus Christ... It's not only for the sake of the Christian gospel, it's for the sake of our responsibility in our society. It's a socially disastrous, community destroying thing to deny that there is a truth that binds us together—Christian and Jew and Muslim and believer and nonbeliever and atheist and secular and black and white and Asian (28-29).So, perhaps we do have an Areopagus, like Paul, where we can proclaim "the unknown god". But how do we go about doing so? Neuhaus cautions,

But we have to demonstrate that we, as Christians, have understood... how Christians claiming to possess the truth can indeed be destructive of public discourse. Christians who are overwhelmingly confident that they actually possess the truth in the sense of being in control of the truth [emphasis mine] can become the enemies of civil discourse (36).Or, as William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury is reputed to have said, "It's possible to be right repugnantly." If you want a concrete example of this, think of the Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, Kansas, and their anti-homosexual-themed picketing of funerals of soldiers killed in Iraq.

I agree with Neuhaus that we who follow Jesus have an obligation and responsibility to declare that there is such a thing as truth. And the only way I see to avoid the pitfall becoming the enemies of civil discourse is to carry on those conversations in the context of relationships forged in our community.

I look forward to reading more of this book. I anticipate it will provide more fodder for this blog!

*InterVarsity Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8308-3845-5

Sunday, January 9, 2011

oh no! the de-christmasification process has begun!

I'm hiding out, really. You need to know that my bride is the Queen of Christmas, and it is always like pulling teeth when we get to January 6th—the Epiphany. Because it is then, you see, that all the decor must come down. Susan is always resistant, and we have the annual tug-of-war between my need to not look like a complete idiot to the neighbors (most of whom took their decorations down and threw their trees out on January 2) and her love of Christmastide.

She usually wins, at least for a couple of days.

Today is the 9th, and she is de-christmasifying the house. But she is not particularly happy about it. I know it will take probably 24 hours before I can strip the lights from the tree and get it out, hopefully with a minimum of needle dispersal on the way out the door. I am not certain we are within the time allotted by the city for curbside removal of the dead trees and wreaths... but hope springs eternal.

The biggest reason she so adores the season is that Susan really does get Christmas. It is not just the nostalgic watching of Capra and Crosby. It's not only the eggnog laced liberally with nutmeg, or the "fluffy eggs" Christmas breakfast (which this year we moved to dinner!). It is her deep understanding that God came to rescue her, that the Child in a feed trough is not some sweet and sentimental story, but one filled with blood and earth. It is fierce and tragic, and it is a story of amazing love and sacrifice. It cost God everything to rescue her; and she knows it.